↧

Survivor or Savior

↧

Book Review: The Year's Best Horror Stories: Series X

Book Review: 'The Year's Best Horror Stories: Series X' edited by Karl Edward Wagner

2 / 5 Stars

‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X’ is DAW Book No. 493 (240 pp) and was published in August, 1982. The striking cover artwork is by Michael Whelan.

All of the stories in this volume were first published in 1980 or 1981, in 'slick' magazines or small press anthologies.

In his Introduction, editor Wagner provides an overview of the genre in 1981, covering both new and failing print outlets for horror fiction. Wagner also notes that, with volume X, The Year’s Best Horror Stories series has achieved the ten-year mark, with the first volume being ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: No. 1’, DAW Books No. 13, released in the US in 1971.

Wagner had an unfortunate affinity for the work of the grossly over-rated Ramsey Campbell, not only foisting two Campbell stories on readers of Series X, but also doing so for other DAW volumes, such as Series XVII.

In this volume, we are given ‘Through the Walls’, which has something to do – deep within its remarkably bad prose – with a suburban husband undergoing a nervous breakdown. Campbell actually uses the sentence: The hinges of the gate shrieked jaggedly; Pears felt as if the sound were being dragged through his ears. The entire story is crammed with these metaphors, all of them straight out of a 'how not to write fiction' class.

Campbell’s other contribution, ‘The Trick’, deals with Halloween in the UK, and the neighborhood bag lady, who may be a witch. This tale is more accessible than ‘Through the Walls’ but still suffers from such clotted, figurative prose that wading through it was tedious.

The other entries in ‘Series X’ are of varying quality. ‘Touring’, By Dozois, Dann, and Swanwick, meshes rock and roll with ghosts. ‘Homecoming’, by Howard Goldsmith, is an embarrassingly bad haunted-house tale.

There are two entries in the classic English Ghost Story mode. ‘Wyntours’, by David G. Rowlands, and ‘Old Hobby Horse’, by A. F. Kidd, adhere to this genre without adding anything really new or novel.

‘Firstborn’, by David Campton, features a remote estate, an eccentric uncle, and a strange greenhouse; there is a Roald Dahl-ish quality to this story that makes it one of the better ones in the anthology.

The obligatory Charles L. Grant story, ‘Every Time You Say I Love You’, is actually one of his better stories, featuring an ending that, unlike so many of his other short stories, delivers a neat payoff.

The mandatory Dennis Etchison entry, ‘The Dark Country’ has nothing to do with horror, being more of a psychological drama involving dissipated American tourists loose in Acapulco. Even as a psychological drama it is over-written and plodding.

‘Luna’, by G. W. Perriwils, features an astronaut troubled by unusual nightmares. ’Mind’, by Les Freeman, deals with a day-tripper to the English town of Whitby; the trains service offers something out of the ordinary.

The magazine Running Times was source for David Clayton Carrad’s ‘Competition’, about a jogger who takes a turn down a forbidding causeway; it’s another of the better tales in the collection.

‘On 202’, by Jeff Hecht, centers on a late-night drive through spooky New England countryside.

M. John Harrison’s ‘Egnaro’ is a tale about a middle-aged bookshop owner whose life is afflicted with entropy. He seeks salvation in the existence of the eponymous mythical country. While well-written, 'Egnaro' is devoid of any horror content, and its inclusion either a sign of how slim the pickings were, or Wagner’s limited capabilities as an anthology editor.

The final entry, Harlan Ellison’s ‘Broken Glass’, deals with telepathy gone bad. It’s rather graphic sexual content is something of a surprise to encounter in a ‘Year’s Best’ anthology, and indicates that Wagner was willing to embrace this aspect of horror fiction, even as he deliberately avoided entertaining any submissions with graphic violence.

The verdict ? ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X’ has a couple of worthwhile entries, but the rest are mediocre. It’s a pretty clear picture of the genre as it stood in the early 80s, a genre experiencing increasing commercial success, primarily due to the novels of Stephen King, but also a genre that, in the main, was content to recycle the same old tropes and plot devices.

Although in the early 80s James Herbert and Shaun Hutson were bravely promoting fiction with genuine horror content, the advent of Clive Barker and ‘The Books of Blood’, and the much-needed changes essential to the emancipation of the genre, were still three years in the future.

2 / 5 Stars

‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X’ is DAW Book No. 493 (240 pp) and was published in August, 1982. The striking cover artwork is by Michael Whelan.

All of the stories in this volume were first published in 1980 or 1981, in 'slick' magazines or small press anthologies.

In his Introduction, editor Wagner provides an overview of the genre in 1981, covering both new and failing print outlets for horror fiction. Wagner also notes that, with volume X, The Year’s Best Horror Stories series has achieved the ten-year mark, with the first volume being ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: No. 1’, DAW Books No. 13, released in the US in 1971.

Wagner had an unfortunate affinity for the work of the grossly over-rated Ramsey Campbell, not only foisting two Campbell stories on readers of Series X, but also doing so for other DAW volumes, such as Series XVII.

In this volume, we are given ‘Through the Walls’, which has something to do – deep within its remarkably bad prose – with a suburban husband undergoing a nervous breakdown. Campbell actually uses the sentence: The hinges of the gate shrieked jaggedly; Pears felt as if the sound were being dragged through his ears. The entire story is crammed with these metaphors, all of them straight out of a 'how not to write fiction' class.

Campbell’s other contribution, ‘The Trick’, deals with Halloween in the UK, and the neighborhood bag lady, who may be a witch. This tale is more accessible than ‘Through the Walls’ but still suffers from such clotted, figurative prose that wading through it was tedious.

The other entries in ‘Series X’ are of varying quality. ‘Touring’, By Dozois, Dann, and Swanwick, meshes rock and roll with ghosts. ‘Homecoming’, by Howard Goldsmith, is an embarrassingly bad haunted-house tale.

There are two entries in the classic English Ghost Story mode. ‘Wyntours’, by David G. Rowlands, and ‘Old Hobby Horse’, by A. F. Kidd, adhere to this genre without adding anything really new or novel.

‘Firstborn’, by David Campton, features a remote estate, an eccentric uncle, and a strange greenhouse; there is a Roald Dahl-ish quality to this story that makes it one of the better ones in the anthology.

The obligatory Charles L. Grant story, ‘Every Time You Say I Love You’, is actually one of his better stories, featuring an ending that, unlike so many of his other short stories, delivers a neat payoff.

The mandatory Dennis Etchison entry, ‘The Dark Country’ has nothing to do with horror, being more of a psychological drama involving dissipated American tourists loose in Acapulco. Even as a psychological drama it is over-written and plodding.

‘Luna’, by G. W. Perriwils, features an astronaut troubled by unusual nightmares. ’Mind’, by Les Freeman, deals with a day-tripper to the English town of Whitby; the trains service offers something out of the ordinary.

The magazine Running Times was source for David Clayton Carrad’s ‘Competition’, about a jogger who takes a turn down a forbidding causeway; it’s another of the better tales in the collection.

‘On 202’, by Jeff Hecht, centers on a late-night drive through spooky New England countryside.

M. John Harrison’s ‘Egnaro’ is a tale about a middle-aged bookshop owner whose life is afflicted with entropy. He seeks salvation in the existence of the eponymous mythical country. While well-written, 'Egnaro' is devoid of any horror content, and its inclusion either a sign of how slim the pickings were, or Wagner’s limited capabilities as an anthology editor.

The final entry, Harlan Ellison’s ‘Broken Glass’, deals with telepathy gone bad. It’s rather graphic sexual content is something of a surprise to encounter in a ‘Year’s Best’ anthology, and indicates that Wagner was willing to embrace this aspect of horror fiction, even as he deliberately avoided entertaining any submissions with graphic violence.

The verdict ? ‘The Year’s Best Horror Stories: Series X’ has a couple of worthwhile entries, but the rest are mediocre. It’s a pretty clear picture of the genre as it stood in the early 80s, a genre experiencing increasing commercial success, primarily due to the novels of Stephen King, but also a genre that, in the main, was content to recycle the same old tropes and plot devices.

Although in the early 80s James Herbert and Shaun Hutson were bravely promoting fiction with genuine horror content, the advent of Clive Barker and ‘The Books of Blood’, and the much-needed changes essential to the emancipation of the genre, were still three years in the future.

↧

↧

The Age of Darkness by Caza

'The Age of Darkness' by Caza

Caza is the pseudonym used by the French artist Philippe Cazaumayou (b. 1941).

Caza was a regular contributor to the magazine Metal Hurlant, which began publishing in France in December 1974.

In the mid-70s Leonard Mogel, the owner and publisher of The National Lampoon magazine in the US, was visiting France and saw a copy of Metal Hurlant. Impressed, he obtained the licensing rights to produce an American version of the magazine. Heavy Metal debuted in April, 1977.

It frequently incorporated translated versions of Metal Hurlant stories, and during the late 70s and early 80s, those of Caza were present in almost every monthly issue of Heavy Metal.

HM's use of higher-resolution printing plates, and ‘slick’ paper stock, well served the crisp colors and highly detailed line work of Caza’s black-and-white, and color, stories.

Accomplished as a draftsman, Caza also displayed considerable skill as a writer, particularly within the confines of the 4 - 10 page story, the lengths he used for most of his contributions. While most of his Metal stories relied on offbeat, quirky humor, when he chose to explore the horror and action genres, his work continued to be of consistent quality.

The Heavy Metal editorial staff made much of the contributions of Moebius (the late Jean Giraud) but in my opinion, Caza’s work was equal to, if not oftentimes superior to, the graphic work of Moebius.

Sadly, a number of Caza’s most impressive Metal Hurlant stories never made it into the pages of Heavy Metal, and an English-language compilation of Caza’s Metal Hurlant / Heavy Metal work has yet to appear. The best effort to date remains 1987's trade paperback Escape from Suburbia, which compiled 12 comics, most of which appeared in Heavy Metal.

As well, ebooks of some of Caza's work are available at his online store.

Caza fans do have at their disposal ‘The Age of Darkness’, published in 1998, in English, in full-color.

'The Age of Darkness' doesn’t provide much information on the origin of the comics presented in this volume, but judging by the artist’s signatures, they were produced during the interval from 1980 to 1997. Some (all ? ) of them appeared in Heavy Metal magazine in the 70s and 80s.

The 14 stories in ‘Age’ are all loosely related, and can be read as standalone entries. Most revolve around the sometimes violent interactions between the mutants or free-spirits who roam the wastelands, and a race of humanoids called ‘Oms’, who resemble the ‘Weebles’ children’s toys from the 1970s (‘Weebles Wobble, But They Don’t Fall Down’).

The Oms represent a regimented, sterile, mechanized society that retreats from the dangerous, but also more vibrant, natural world outside their gates. They are depicted with some degree of pathos.

Caza’s artwork is stunning in its detail and use of color, and is ably reproduced in this book. Although each entry rarely is longer than 5 - 6 pages, the plots are well-composed and display quirky humor, horror, and pathos.

Readers who appreciate quality graphic art, and a European sensibility to the sf genre, will want to get a copy of ‘The Age of Darkness’.

[ I was able to purchase 'The Age of Darkness' from the Heavy Metal online store, where it was available for $12.95, in Fall 2012. As of October 2013, there still are copies in stock at the Heavy Metal online store. There are copies available at amazon, but for exorbitant prices.]

Here is 'Nighttime' (1980) from 'The Age of Darkness'. A neat, nasty little horror tale.....

Caza is the pseudonym used by the French artist Philippe Cazaumayou (b. 1941).

Caza was a regular contributor to the magazine Metal Hurlant, which began publishing in France in December 1974.

In the mid-70s Leonard Mogel, the owner and publisher of The National Lampoon magazine in the US, was visiting France and saw a copy of Metal Hurlant. Impressed, he obtained the licensing rights to produce an American version of the magazine. Heavy Metal debuted in April, 1977.

It frequently incorporated translated versions of Metal Hurlant stories, and during the late 70s and early 80s, those of Caza were present in almost every monthly issue of Heavy Metal.

HM's use of higher-resolution printing plates, and ‘slick’ paper stock, well served the crisp colors and highly detailed line work of Caza’s black-and-white, and color, stories.

Accomplished as a draftsman, Caza also displayed considerable skill as a writer, particularly within the confines of the 4 - 10 page story, the lengths he used for most of his contributions. While most of his Metal stories relied on offbeat, quirky humor, when he chose to explore the horror and action genres, his work continued to be of consistent quality.

The Heavy Metal editorial staff made much of the contributions of Moebius (the late Jean Giraud) but in my opinion, Caza’s work was equal to, if not oftentimes superior to, the graphic work of Moebius.

Sadly, a number of Caza’s most impressive Metal Hurlant stories never made it into the pages of Heavy Metal, and an English-language compilation of Caza’s Metal Hurlant / Heavy Metal work has yet to appear. The best effort to date remains 1987's trade paperback Escape from Suburbia, which compiled 12 comics, most of which appeared in Heavy Metal.

As well, ebooks of some of Caza's work are available at his online store.

Caza fans do have at their disposal ‘The Age of Darkness’, published in 1998, in English, in full-color.

'The Age of Darkness' doesn’t provide much information on the origin of the comics presented in this volume, but judging by the artist’s signatures, they were produced during the interval from 1980 to 1997. Some (all ? ) of them appeared in Heavy Metal magazine in the 70s and 80s.

The 14 stories in ‘Age’ are all loosely related, and can be read as standalone entries. Most revolve around the sometimes violent interactions between the mutants or free-spirits who roam the wastelands, and a race of humanoids called ‘Oms’, who resemble the ‘Weebles’ children’s toys from the 1970s (‘Weebles Wobble, But They Don’t Fall Down’).

The Oms represent a regimented, sterile, mechanized society that retreats from the dangerous, but also more vibrant, natural world outside their gates. They are depicted with some degree of pathos.

Caza’s artwork is stunning in its detail and use of color, and is ably reproduced in this book. Although each entry rarely is longer than 5 - 6 pages, the plots are well-composed and display quirky humor, horror, and pathos.

Readers who appreciate quality graphic art, and a European sensibility to the sf genre, will want to get a copy of ‘The Age of Darkness’.

[ I was able to purchase 'The Age of Darkness' from the Heavy Metal online store, where it was available for $12.95, in Fall 2012. As of October 2013, there still are copies in stock at the Heavy Metal online store. There are copies available at amazon, but for exorbitant prices.]

Here is 'Nighttime' (1980) from 'The Age of Darkness'. A neat, nasty little horror tale.....

↧

The Canal by Corben

↧

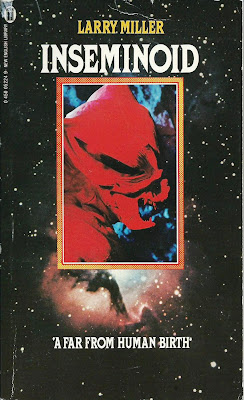

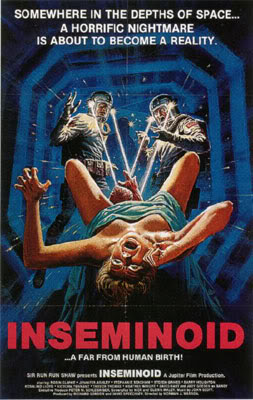

Book Review: Inseminoid

Book Review: 'Inseminoid' by Larry Miller

1 / 5 Stars

This novelization of 'Inseminoid' (158 pp) was released in April, 1981 by UK publisher New English Library.

Team Nova is an archeology expedition housed in an installation on a remote planet. In the course of excavating some ancient ruins, the team discovers a burial crypt containing a deceased alien creature, preserved in a sealed, coffin-like chamber.

When the alien is returned to the laboratory, it gradually comes back to life, to the astonishment of the crew. However, their carelessness about securing the alien proves their undoing, as the creature succeeds in escaping, and rapes crewmember Sandy.

The hapless Sandy rapidly devolves into a pregnant, homicidal quasi-alien, endangering the lives of the rest of the crew. Can the surviving members of Team Nova kill Sandy…or will she succeed in giving birth to the alien offspring ?

I never saw more than brief snatches of trailers of ‘Inseminoid’ when it was released back in the early 80s. Needless to say, the segments I did see confirmed the film’s low-budget, schlocky underpinnings. The film did have a strong cast of veteran British actors, including Stephanie Beacham (‘Dynasty’, ‘Beverly Hills, 90210’), Victoria Tennant (‘Flowers in the Attic’), and Judy Geeson (‘Star Trek Voyager’).

The novelization differs from the film in terms of selected scenes and events (i.e., the fate of Sandy). But not unsurprisingly, the novelization really fails to improve on the original script, in terms of making a dud narrative into something worthwhile. Some of the goofy contrivances that take place in ‘Inseminoid’ exist for no other reason than to provide the film with an opportunity to display disemboweled corpses, a la Alien.

What little suspense that exists in the narrative comes about mainly because the crewmembers of Team Nova are abysmally stupid and clumsy. In the end, I wound up rooting for the monster, if only because so many of the horny, dim-witted crew-members deserved to die.

In summary, even the most dedicated fans of Bad Films may want to pass on the novel or DVD of 'Inseminoid'.

1 / 5 Stars

In the aftermath of the success of the 20thCentury Fox film ‘Alien’ in the Summer of 1979, schlock producers released a stream of low-budget imitations: ‘Alien Contamination’ (1980) ; ‘Inseminoid’ (aka ‘Horror Planet’) (1981); ‘Parasite’ (1982); and ‘Xtro’ (1982).

This novelization of 'Inseminoid' (158 pp) was released in April, 1981 by UK publisher New English Library.

Team Nova is an archeology expedition housed in an installation on a remote planet. In the course of excavating some ancient ruins, the team discovers a burial crypt containing a deceased alien creature, preserved in a sealed, coffin-like chamber.

When the alien is returned to the laboratory, it gradually comes back to life, to the astonishment of the crew. However, their carelessness about securing the alien proves their undoing, as the creature succeeds in escaping, and rapes crewmember Sandy.

The hapless Sandy rapidly devolves into a pregnant, homicidal quasi-alien, endangering the lives of the rest of the crew. Can the surviving members of Team Nova kill Sandy…or will she succeed in giving birth to the alien offspring ?

I never saw more than brief snatches of trailers of ‘Inseminoid’ when it was released back in the early 80s. Needless to say, the segments I did see confirmed the film’s low-budget, schlocky underpinnings. The film did have a strong cast of veteran British actors, including Stephanie Beacham (‘Dynasty’, ‘Beverly Hills, 90210’), Victoria Tennant (‘Flowers in the Attic’), and Judy Geeson (‘Star Trek Voyager’).

The novelization differs from the film in terms of selected scenes and events (i.e., the fate of Sandy). But not unsurprisingly, the novelization really fails to improve on the original script, in terms of making a dud narrative into something worthwhile. Some of the goofy contrivances that take place in ‘Inseminoid’ exist for no other reason than to provide the film with an opportunity to display disemboweled corpses, a la Alien.

What little suspense that exists in the narrative comes about mainly because the crewmembers of Team Nova are abysmally stupid and clumsy. In the end, I wound up rooting for the monster, if only because so many of the horny, dim-witted crew-members deserved to die.

In summary, even the most dedicated fans of Bad Films may want to pass on the novel or DVD of 'Inseminoid'.

↧

↧

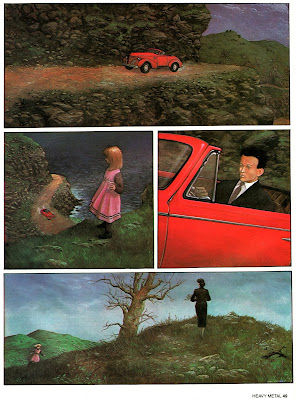

Heavy Metal October 1983

'Heavy Metal' magazine October 1983

October, 1983, and in heavy rotation on FM radio and MTV is 'In A Big Country' by the Scottish New Wave band, Big Country.

The October 1983 issue of Heavy Metal magazine features a front cover by Luis Royo, and a back cover (a portrait of Ranxerox) by Liberatore.

The Dossier section opens with an interview with a documentary film-maker about his recent work, a film about Bob Dylan. By 1983 Dylan had lapsed into well-deserved obscurity, and this film did little to resurrect his career, which would be effectively killed once and for all by a disastrous performance at the close of the Live Aid concert in 1985.

The Dossier moves on to a brief overview of Harlan Ellison's literary career; an advertisement for the biography Loving John [Lennon] by former girlfriend May Pang; and a cultural analysis of the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoon (?)........ it must've been a slow month for Dossier content.

John Glen, director of the just-released Bond film Octopussy, gets an interview,as does the director Walter Hill.

For the comics content, the October issue offers up new installments of 'Tex Arcana', 'The Odyssey' by Navarro and Sauri, 'The Third Song', by Jodorowsky and Arno, and 'Ranxerox', by Tamburini and Liberatore.

Perhaps the best strip in the issue is another of the 'red convertible' tales by Didier Eberoni, this one titled 'Nimble Fingers', with a plot by Rodolphe.

Its existential theme is well-served by the great artwork of Eberoni, whose meticulous rendering of the grassy fields, the tree branches and twigs, and the contours of the rocks.

October, 1983, and in heavy rotation on FM radio and MTV is 'In A Big Country' by the Scottish New Wave band, Big Country.

The October 1983 issue of Heavy Metal magazine features a front cover by Luis Royo, and a back cover (a portrait of Ranxerox) by Liberatore.

The Dossier section opens with an interview with a documentary film-maker about his recent work, a film about Bob Dylan. By 1983 Dylan had lapsed into well-deserved obscurity, and this film did little to resurrect his career, which would be effectively killed once and for all by a disastrous performance at the close of the Live Aid concert in 1985.

The Dossier moves on to a brief overview of Harlan Ellison's literary career; an advertisement for the biography Loving John [Lennon] by former girlfriend May Pang; and a cultural analysis of the Rocky and Bullwinkle cartoon (?)........ it must've been a slow month for Dossier content.

John Glen, director of the just-released Bond film Octopussy, gets an interview,as does the director Walter Hill.

For the comics content, the October issue offers up new installments of 'Tex Arcana', 'The Odyssey' by Navarro and Sauri, 'The Third Song', by Jodorowsky and Arno, and 'Ranxerox', by Tamburini and Liberatore.

Perhaps the best strip in the issue is another of the 'red convertible' tales by Didier Eberoni, this one titled 'Nimble Fingers', with a plot by Rodolphe.

Its existential theme is well-served by the great artwork of Eberoni, whose meticulous rendering of the grassy fields, the tree branches and twigs, and the contours of the rocks.

↧

Book Review: The Black Horde

Book Review: 'The Black Horde' by Richard Lewis

2 / 5 Stars

‘The Black Horde’ (166 pp., Signet, October 1980) was first published in the UK in 1979 under the title ‘Devil’s Coach Horse’. (The ‘Devil’s Coach Horse’ is a soil-dwelling rove beetle that lives in the UK).

Richard (E.) Lewis has written a large number of novels for the adult and young adult markets. ‘The Black Horde’, along with his other novel ‘The Spiders’ (1987), doesn’t pretend to be anything other than the literary equivalent of the low-budget, ‘monster of the week’ movies that appear on the SyFy Channel.

The plot is simple and direct: John Masters, a British entomologist, discovers a new species of rove beetle, resembling the Devil’s Coach Horse beetle, overseas, and is carrying live specimens back to the UK when his plane crashes in the Alps. With the coming of Spring and the melting of the snow, his corpse is recovered from the mountain top and shipped home.

It turns out that the enterprising beetles have used Masters' body as an impromptu shelter, and they emerge from the corpse at a British mortuary and escape into the wild. This is in fact a disaster in the making.

For these are not ordinary rove beetles, preying on small insects; instead, these rove beetles prefer the taste of human flesh. And with their sharp mandibles, they can chew their way into exposed skin in a matter of seconds. Once embedded in the internal organs of their victim, the beetles lay eggs, which rapidly hatch into flesh-eating larvae, which in turn mature into pupae, and then adult beetles, completing the cycle.

Young entomologist Paul Adams, a colleague of the departed Masters, finds himself called in as a subject matter expert when the police receive disturbing reports of people being eaten alive by beetles. As Adams and the authorities soon learn, these isolated incidents are the forerunners of much greater horror to come, as the beetle population expands and swarms of hungry insects trespass on the English countryside in a frenzied search for warm, sustaining flesh….

‘The Black Horde’ shows considerable influence from the horror novelist James Herbert, adopting the clipped, declarative prose style favored by that author and the regular inclusion of passages of gore and grue.

As with many of Herbert’s novels, ‘The Black Horde’ alternates its main narrative with vignettes in which people – most often couples having sex – find themselves at risk of a bloody, painful, terrifying death at the mandibles of the ravenous beetles.

I can’t recommend ‘The Black Horde’ as a masterful example of the horror genre, but if you are looking for a brief ‘pulp’ read, something on the order of a James Herbert out-take, it fits the bill.

2 / 5 Stars

‘The Black Horde’ (166 pp., Signet, October 1980) was first published in the UK in 1979 under the title ‘Devil’s Coach Horse’. (The ‘Devil’s Coach Horse’ is a soil-dwelling rove beetle that lives in the UK).

Richard (E.) Lewis has written a large number of novels for the adult and young adult markets. ‘The Black Horde’, along with his other novel ‘The Spiders’ (1987), doesn’t pretend to be anything other than the literary equivalent of the low-budget, ‘monster of the week’ movies that appear on the SyFy Channel.

The plot is simple and direct: John Masters, a British entomologist, discovers a new species of rove beetle, resembling the Devil’s Coach Horse beetle, overseas, and is carrying live specimens back to the UK when his plane crashes in the Alps. With the coming of Spring and the melting of the snow, his corpse is recovered from the mountain top and shipped home.

It turns out that the enterprising beetles have used Masters' body as an impromptu shelter, and they emerge from the corpse at a British mortuary and escape into the wild. This is in fact a disaster in the making.

For these are not ordinary rove beetles, preying on small insects; instead, these rove beetles prefer the taste of human flesh. And with their sharp mandibles, they can chew their way into exposed skin in a matter of seconds. Once embedded in the internal organs of their victim, the beetles lay eggs, which rapidly hatch into flesh-eating larvae, which in turn mature into pupae, and then adult beetles, completing the cycle.

Young entomologist Paul Adams, a colleague of the departed Masters, finds himself called in as a subject matter expert when the police receive disturbing reports of people being eaten alive by beetles. As Adams and the authorities soon learn, these isolated incidents are the forerunners of much greater horror to come, as the beetle population expands and swarms of hungry insects trespass on the English countryside in a frenzied search for warm, sustaining flesh….

‘The Black Horde’ shows considerable influence from the horror novelist James Herbert, adopting the clipped, declarative prose style favored by that author and the regular inclusion of passages of gore and grue.

As with many of Herbert’s novels, ‘The Black Horde’ alternates its main narrative with vignettes in which people – most often couples having sex – find themselves at risk of a bloody, painful, terrifying death at the mandibles of the ravenous beetles.

I can’t recommend ‘The Black Horde’ as a masterful example of the horror genre, but if you are looking for a brief ‘pulp’ read, something on the order of a James Herbert out-take, it fits the bill.

↧

The Vampire Cinema

'The Vampire Cinema' by David Pirie

Back in the 1970s, before there was an internet, or an amazon.com, one primary way to acquire PorPor books was via the companies that specialized in selling remainders through mass-mailed catalogs.

One of the larger such companies was Publishers Central Bureau, or PCB. Their distinctive two-tone catalogs regularly would arrive at my house as part of the junk mail.

'The Vampire Cinema', published in 1977 by Quarto Books, was a perennial entrant in the PCB catalog, and in late 1978 I ordered it.

'The Vampire Cinema' is actually a pretty good overview of vampire movies up till the early 70s. It's well illustrated with copious, often full-page, color, black and white, and tinted stills.

Pirie's chapters start off with a look at vampires in popular fiction and mythology; move on to the early vampire films, such as Nosferatu; the Universal films featuring Bella Lugosi; and then the Hammer vampire films, staring Christopher Lee as Count Dracula.

The chronology then moves to the Eurotrash, low-budget 'sex' vampire films of such directors as Jean Rollin and Roger Vadim. Blurring the lines between softcore porn and art house horror, this sub-genre also was exploited by Hammer, with early 70s movies such as The Vampire Lovers, Twins of Evil, Countess Dracula, and Lust for a Vampire.

The book's final chapters touch on the mixed success Hammer experienced with taking its Dracula series to the 20th century, as well as an overview of the 'New American' vampire films of the 70s, such as Blacula and Count Yorga.

Pirie makes the argument that the American low-budget horror cinema made a crucial transition in subject matter, taking the European image of the vampire as a seductive aristocrat, and converting it into a zombie or ghoul with a more grim and unglamorous aesthetic.

'The Vampire Cinema' closes with a brief overview of The Latin Vampire, as epitomized by Spanish and Italian productions of the 60s and 70s.

I suspect that anyone under 30, exposed to the tsunami of vampire content dominating today's popular culture, is going to find the content of 'The Vampire Cinema' to be quirky and quaint.

The book's most appreciative audience will probably be found among those who subscribe to Shock Cinema and search the cult cinema websites for the DVDs available for some, but not all, of the films covered in 'The Vampire Cinema'. In other words, those who grew up in the 60s and 70s and still have a nostalgic fondness for the Old School approach to horror movies.

This book is for you....and copies can be found at the usual online sources for under $10.

Back in the 1970s, before there was an internet, or an amazon.com, one primary way to acquire PorPor books was via the companies that specialized in selling remainders through mass-mailed catalogs.

One of the larger such companies was Publishers Central Bureau, or PCB. Their distinctive two-tone catalogs regularly would arrive at my house as part of the junk mail.

'The Vampire Cinema', published in 1977 by Quarto Books, was a perennial entrant in the PCB catalog, and in late 1978 I ordered it.

'The Vampire Cinema' is actually a pretty good overview of vampire movies up till the early 70s. It's well illustrated with copious, often full-page, color, black and white, and tinted stills.

Pirie's chapters start off with a look at vampires in popular fiction and mythology; move on to the early vampire films, such as Nosferatu; the Universal films featuring Bella Lugosi; and then the Hammer vampire films, staring Christopher Lee as Count Dracula.

The chronology then moves to the Eurotrash, low-budget 'sex' vampire films of such directors as Jean Rollin and Roger Vadim. Blurring the lines between softcore porn and art house horror, this sub-genre also was exploited by Hammer, with early 70s movies such as The Vampire Lovers, Twins of Evil, Countess Dracula, and Lust for a Vampire.

The book's final chapters touch on the mixed success Hammer experienced with taking its Dracula series to the 20th century, as well as an overview of the 'New American' vampire films of the 70s, such as Blacula and Count Yorga.

Pirie makes the argument that the American low-budget horror cinema made a crucial transition in subject matter, taking the European image of the vampire as a seductive aristocrat, and converting it into a zombie or ghoul with a more grim and unglamorous aesthetic.

'The Vampire Cinema' closes with a brief overview of The Latin Vampire, as epitomized by Spanish and Italian productions of the 60s and 70s.

I suspect that anyone under 30, exposed to the tsunami of vampire content dominating today's popular culture, is going to find the content of 'The Vampire Cinema' to be quirky and quaint.

The book's most appreciative audience will probably be found among those who subscribe to Shock Cinema and search the cult cinema websites for the DVDs available for some, but not all, of the films covered in 'The Vampire Cinema'. In other words, those who grew up in the 60s and 70s and still have a nostalgic fondness for the Old School approach to horror movies.

This book is for you....and copies can be found at the usual online sources for under $10.

↧

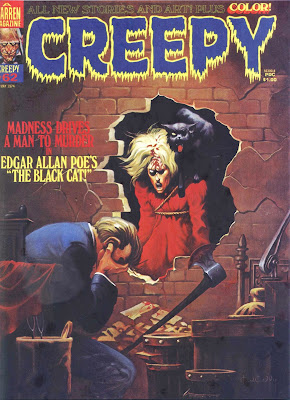

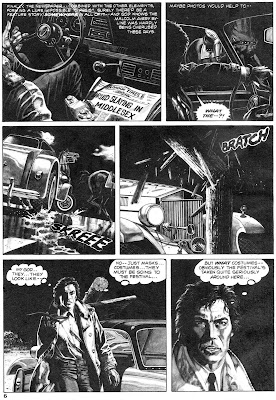

Blood on Black Satin episode one

'Blood on Black Satin' episode one

by Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy

Episode One (from Eerie #109, February 1980)

One of the most impressive strips ever to appear in a Warren magazine was the three-part 'Blood on Black Satin', written by Doug Moench, and gifted with outstanding artwork by Paul Gulacy.

The inaugural installment appeared in Eerie 109 (February 1980) and parts two and three in issues 110 (April 1980) and 111 (June 1980).

Posted below is the first episode; the succeeding episodes will be posted in the future here at the PorPor Books blog.

These scans are taken from the original comic and done at 300 dpi, using the graytone setting on my Plustek book scanner. I then used Corel Photo-Paint to autoadjust the images for fading and sharpness, although this creates jpeg files each 18 - 22 MB in size - hopefully the web page won't crash when loading.

For reasons that are unclear, some of the pages present with a sepia tint, despite being auto-adjusted; I suspect this is an issue with Blogger, as when I examine the images in Photo-Paint, they display no tinting.

I expect they will be as good as one can get, at least until Dark Horse / The New Comic Company produce all three episodes in an upcoming Eerie Presents hardbound volume....

by Doug Moench and Paul Gulacy

Episode One (from Eerie #109, February 1980)

One of the most impressive strips ever to appear in a Warren magazine was the three-part 'Blood on Black Satin', written by Doug Moench, and gifted with outstanding artwork by Paul Gulacy.

The inaugural installment appeared in Eerie 109 (February 1980) and parts two and three in issues 110 (April 1980) and 111 (June 1980).

Posted below is the first episode; the succeeding episodes will be posted in the future here at the PorPor Books blog.

These scans are taken from the original comic and done at 300 dpi, using the graytone setting on my Plustek book scanner. I then used Corel Photo-Paint to autoadjust the images for fading and sharpness, although this creates jpeg files each 18 - 22 MB in size - hopefully the web page won't crash when loading.

For reasons that are unclear, some of the pages present with a sepia tint, despite being auto-adjusted; I suspect this is an issue with Blogger, as when I examine the images in Photo-Paint, they display no tinting.

I expect they will be as good as one can get, at least until Dark Horse / The New Comic Company produce all three episodes in an upcoming Eerie Presents hardbound volume....

↧

↧

Book Review: Lycanthia

Book Review: 'Lycanthia' by Tanith Lee

3 / 5 Stars

‘Lycanthia, or The Children of Wolves’ (220 pp) is DAW Book No. 429, and was published in April, 1981. The cover artwork is by Paul Chadwick.

‘Lycanthia’ is in many ways a forerunner of the highly successful genre of ‘supernatural’ romances (e.g., 'Twilight'), a genre that really didn’t exist back in 1981.

The novel is set in France during the 1920s or 1930s. Its protagonist is Christian Dorse, a young man utterly absorbed with himself, and the tuberculosis that is slowly killing him.

As the novel opens, Dorse has the good luck to inherit a chateau in the remote countryside. Bored with city life, and conscious of his dwindling years, Dorse travels to the chateau, and the opening chapters introduce the reader to the melancholy Winter countryside, the foreboding mansion, its eccentric servants, and the local village, with its ancient superstitions and strange customs.

At first content to play the cynical aesthete, stylishly prostrated by his illness, Dorse learns that the chateau has a history of disturbing behaviors by its former seigneurs. There are intimations of crimes and atrocities, acts that may have links to the presence of the large black dogs haunting the chateau and the surrounding forests.

Dorse soon finds himself walking the narrow trails in the woods with a rifle in his hands, seeking what may be man-killing wolves.But what he actually finds is something more complex than a simple folktale of loups-garoux. For the village, the chateau, and the rumored werewolves all are part of an ancient and enduring tragedy, a tragedy that he may unwittingly revive…..

As was the case with most of Tanith Lee’s output in the 70s and 80s, ‘Lycanthia’ relies heavily on an ornate prose style. Readers should prepare for sentences chock full of metaphors and similes, and detailed exposition on the mental and spiritual turmoil of a ‘decadent’ character.

Lee clearly is making a conscious effort to imbue her novel with the same themes and attitudes of J. K. Huysmans’ 1884 symbolist classic A Rebours (‘Against Nature’). Christian Dorse is at heart a more modern version of Huysmans’ Jean Des Esseintes, seeking stimulation of his jaded, world-weary palate from the customs and practices of the primitive, but virile, landscape of rural France.

For these reasons, I suspect that ‘Lycanthia’ will not be embraced by readers of modern urban fantasies, where a clean, clear prose style, and recurring casts of characters, are the status quo.

3 / 5 Stars

‘Lycanthia, or The Children of Wolves’ (220 pp) is DAW Book No. 429, and was published in April, 1981. The cover artwork is by Paul Chadwick.

‘Lycanthia’ is in many ways a forerunner of the highly successful genre of ‘supernatural’ romances (e.g., 'Twilight'), a genre that really didn’t exist back in 1981.

The novel is set in France during the 1920s or 1930s. Its protagonist is Christian Dorse, a young man utterly absorbed with himself, and the tuberculosis that is slowly killing him.

As the novel opens, Dorse has the good luck to inherit a chateau in the remote countryside. Bored with city life, and conscious of his dwindling years, Dorse travels to the chateau, and the opening chapters introduce the reader to the melancholy Winter countryside, the foreboding mansion, its eccentric servants, and the local village, with its ancient superstitions and strange customs.

At first content to play the cynical aesthete, stylishly prostrated by his illness, Dorse learns that the chateau has a history of disturbing behaviors by its former seigneurs. There are intimations of crimes and atrocities, acts that may have links to the presence of the large black dogs haunting the chateau and the surrounding forests.

Dorse soon finds himself walking the narrow trails in the woods with a rifle in his hands, seeking what may be man-killing wolves.But what he actually finds is something more complex than a simple folktale of loups-garoux. For the village, the chateau, and the rumored werewolves all are part of an ancient and enduring tragedy, a tragedy that he may unwittingly revive…..

As was the case with most of Tanith Lee’s output in the 70s and 80s, ‘Lycanthia’ relies heavily on an ornate prose style. Readers should prepare for sentences chock full of metaphors and similes, and detailed exposition on the mental and spiritual turmoil of a ‘decadent’ character.

Lee clearly is making a conscious effort to imbue her novel with the same themes and attitudes of J. K. Huysmans’ 1884 symbolist classic A Rebours (‘Against Nature’). Christian Dorse is at heart a more modern version of Huysmans’ Jean Des Esseintes, seeking stimulation of his jaded, world-weary palate from the customs and practices of the primitive, but virile, landscape of rural France.

For these reasons, I suspect that ‘Lycanthia’ will not be embraced by readers of modern urban fantasies, where a clean, clear prose style, and recurring casts of characters, are the status quo.

↧

Father Shandor: The Hordes of Hell from Warrior No. 7

'Father Shandor, Demon Stalker'

'The Hordes of Hell'

from Warrior (UK) No. 7, November, 1982

In this installment, Father Shandor - lately killed by the demon princess Jaramsheela - gets a new lease on life, as Jaramsheela discovers her brother's army is advancing on her realm. Shandor discovers that being brought back from the dead brings with it some striking new powers.....

'The Hordes of Hell'

from Warrior (UK) No. 7, November, 1982

In this installment, Father Shandor - lately killed by the demon princess Jaramsheela - gets a new lease on life, as Jaramsheela discovers her brother's army is advancing on her realm. Shandor discovers that being brought back from the dead brings with it some striking new powers.....

↧

The Graveyard

↧

Book Review: '48

Book Review: '48 by James Herbert

2 / 5 Stars

’48 was published in hardcover in 1997; this Harper Prism paperback (435 pp) was released in 1998.

The novel takes place in an alternate England, which, in March 1945, is bombarded by Nazi V-2 rockets carrying a biowarfare agent called the ‘Blood Death’. The Blood Death causes a gruesome death by hemorrhage, and within a matter of weeks, all but a tiny fraction of the UK’s population has succumbed.

The survivors can be grouped into two cohorts: there are those who have a slight resistance to the Blood Death, and thus are the ‘slow dying’….getting a little sicker with each passing day, a little closer to bleeding out in a final spasm of agony.

Then there are those with blood type AB-negative, the truly immune.

As the novel opens, it’s the Summer of ’48, and the first-person narrator, an American fighter pilot named Eugene Nathaniel Hoke, is lounging in the empty hallways of the Savoy Hotel in London. With the good fortune to be an AB-negative and immune to the plague, when not enjoying having a five-star hotel to his disposal, Hole roams the silent streets of London, carefully ignoring the corpses inside the rusting cars and trucks, lying on the doorsteps of houses, or simply moldering as they lie on the sidewalks and the roadways.

Hoke doesn’t have it all easy, however. A band of slow dying fascists, wearing the uniforms of Britain’s Blackshirts, and led by a psychopath named Hubble, are intent on capturing him. Their goal: transfuse Hoke’s blood into Hubble, in a wild hope that this will arrest the disease, and let Hubble live to establish a fascist state in the ruins of England.

Needless to say, Hoke has no intention of letting himself be drained in order to prolong the life of Hubble, nor any other Blackshirt.

Complications arrive when Hoke discovers that there are other survivors in London….an upper-class society girl named Muriel, a working-class girl named Cissie, and a German POW named Stern. Muriel and Cissie seem like they can be trusted. But Stern may not be what he appears to be….but with Hubble and the Blackshirts right on his tail, Hoke will have to take chances if he is to live another day……..

James Herbert (1943 – 2013) wrote ’48 late in his career, and, rather than another of the horror novels for which he was well-known and highly successful, he was obviously trying to produce an action novel in the Robert Ludlum tradition. But for me, ‘48’ was a disappointment, mainly because it’s essentially one long ‘chase’ novel, and too much of a stretch for Herbert’s abilities.

The ‘Blood Death’ component of the backstory is an afterthought, more of a plot device to provide Herbert with a deserted, Omega Man– style London within which to set his action sequences. The novel also is devoid of any horror or supernatural overtones; unlike the ‘Lair’ series, this ruined metropolis contains no monsters or sci-fi anomalies.

In the absence of any horror or sf content, the reader is left with an increasingly tedious series of hairs-breadth escapes, last –minute reprieves, the just-in-time collapsing of ceilings, guns that happen to jam just when the holder intends to fire, etc., etc.

It doesn’t help things that Hoke is one of stupider characters I've encountered in a Herbert novel, nor that the brief sections of the narrative in which the chase is suspended, are given over to Herbert speechifying about the loathsome nature of Fascism and Bigotry.

The climax of ’48, and the final confrontation between Hoke and the Blackshirts, takes place amid some famous London landmarks. There is some inherent drama in such a setup, but unfortunately, this sequence is so over-written that by the time Herbert closed the novel, I was more than ready for the final paragraph to make its appearance.

In summary, ’48 is for true Herbert aficionados only.

2 / 5 Stars

’48 was published in hardcover in 1997; this Harper Prism paperback (435 pp) was released in 1998.

The novel takes place in an alternate England, which, in March 1945, is bombarded by Nazi V-2 rockets carrying a biowarfare agent called the ‘Blood Death’. The Blood Death causes a gruesome death by hemorrhage, and within a matter of weeks, all but a tiny fraction of the UK’s population has succumbed.

The survivors can be grouped into two cohorts: there are those who have a slight resistance to the Blood Death, and thus are the ‘slow dying’….getting a little sicker with each passing day, a little closer to bleeding out in a final spasm of agony.

Then there are those with blood type AB-negative, the truly immune.

As the novel opens, it’s the Summer of ’48, and the first-person narrator, an American fighter pilot named Eugene Nathaniel Hoke, is lounging in the empty hallways of the Savoy Hotel in London. With the good fortune to be an AB-negative and immune to the plague, when not enjoying having a five-star hotel to his disposal, Hole roams the silent streets of London, carefully ignoring the corpses inside the rusting cars and trucks, lying on the doorsteps of houses, or simply moldering as they lie on the sidewalks and the roadways.

Hoke doesn’t have it all easy, however. A band of slow dying fascists, wearing the uniforms of Britain’s Blackshirts, and led by a psychopath named Hubble, are intent on capturing him. Their goal: transfuse Hoke’s blood into Hubble, in a wild hope that this will arrest the disease, and let Hubble live to establish a fascist state in the ruins of England.

Needless to say, Hoke has no intention of letting himself be drained in order to prolong the life of Hubble, nor any other Blackshirt.

Complications arrive when Hoke discovers that there are other survivors in London….an upper-class society girl named Muriel, a working-class girl named Cissie, and a German POW named Stern. Muriel and Cissie seem like they can be trusted. But Stern may not be what he appears to be….but with Hubble and the Blackshirts right on his tail, Hoke will have to take chances if he is to live another day……..

James Herbert (1943 – 2013) wrote ’48 late in his career, and, rather than another of the horror novels for which he was well-known and highly successful, he was obviously trying to produce an action novel in the Robert Ludlum tradition. But for me, ‘48’ was a disappointment, mainly because it’s essentially one long ‘chase’ novel, and too much of a stretch for Herbert’s abilities.

The ‘Blood Death’ component of the backstory is an afterthought, more of a plot device to provide Herbert with a deserted, Omega Man– style London within which to set his action sequences. The novel also is devoid of any horror or supernatural overtones; unlike the ‘Lair’ series, this ruined metropolis contains no monsters or sci-fi anomalies.

In the absence of any horror or sf content, the reader is left with an increasingly tedious series of hairs-breadth escapes, last –minute reprieves, the just-in-time collapsing of ceilings, guns that happen to jam just when the holder intends to fire, etc., etc.

It doesn’t help things that Hoke is one of stupider characters I've encountered in a Herbert novel, nor that the brief sections of the narrative in which the chase is suspended, are given over to Herbert speechifying about the loathsome nature of Fascism and Bigotry.

The climax of ’48, and the final confrontation between Hoke and the Blackshirts, takes place amid some famous London landmarks. There is some inherent drama in such a setup, but unfortunately, this sequence is so over-written that by the time Herbert closed the novel, I was more than ready for the final paragraph to make its appearance.

In summary, ’48 is for true Herbert aficionados only.

↧

↧

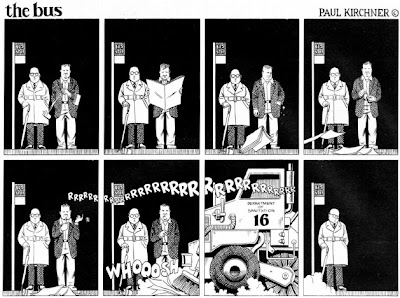

'The Bus'

↧

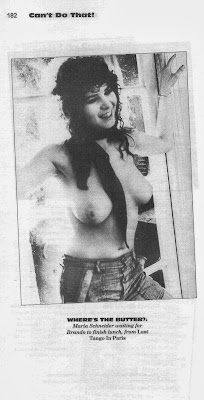

Sex, American Style

'Sex, American Style: An Illustrated Romp Through the Golden Age of Heterosexuality' by Jack Boulware

'Sex, American Style' (248 pp) was published in 1997 by Feral House. It's a large trade paperback, with a format in which copious black and white illustrations occupy the sidebars, and text, the center of the page.

If you grew up in the period from 1968 - 1980, like I did, then this book is a bizarre, but entertaining, trip back in time....to the era when everyone was focused on maintaining their body hair, not removing it.

When there was no internet, no AIDS, no Xanax, and the idea of buying jeans with holes already in them utterly incomprehensible.

Hedonism and self-absorption were the proper attitudes to take in the face of a battered economy, gas shortages, widespread unemployment, and plenty of existential anomie.

Boulware divides the book into chapters dealing with various aspects of American culture. He leads off with movies, both Hollywood productions and hardcore (back in 1971, in order to see porn movies, you actually had to visit an adult theatre).

The next series of chapters explore 70s 'excess' in music....

...literature......

......television.....

.....'how to' manuals........

....consumer products.....

....and the 'swinger' culture....

The verdict ? Having a copy of 'Sex, American Style' is an absolute requirement for anyone who grew up in the interval from 1968 - 1980.

'Sex, American Style' (248 pp) was published in 1997 by Feral House. It's a large trade paperback, with a format in which copious black and white illustrations occupy the sidebars, and text, the center of the page.

If you grew up in the period from 1968 - 1980, like I did, then this book is a bizarre, but entertaining, trip back in time....to the era when everyone was focused on maintaining their body hair, not removing it.

When there was no internet, no AIDS, no Xanax, and the idea of buying jeans with holes already in them utterly incomprehensible.

Hedonism and self-absorption were the proper attitudes to take in the face of a battered economy, gas shortages, widespread unemployment, and plenty of existential anomie.

Boulware divides the book into chapters dealing with various aspects of American culture. He leads off with movies, both Hollywood productions and hardcore (back in 1971, in order to see porn movies, you actually had to visit an adult theatre).

The next series of chapters explore 70s 'excess' in music....

...literature......

......television.....

.....'how to' manuals........

....consumer products.....

....and the 'swinger' culture....

The verdict ? Having a copy of 'Sex, American Style' is an absolute requirement for anyone who grew up in the interval from 1968 - 1980.

↧

The Adventures of Luther Arkwright

'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright' by Bryan Talbot

'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright' has a complicated history.

Throughout the 1970s, British artist Bryan Talbot contributed material to various underground comix being published in the UK, among them Brainstorm Comix.

In 1976, as Talbot recounts in his history of the Arkwright canon, in an issue of Mixed Bunch Comix (a Brainstorm imprint) he drew a seven-page strip titled 'The Papist Affair'. This represented the first appearance of the Luther Arkwright character.

'The Papist Affair' was a humor strip, and in my opinion, it was mainly intended as an opportunity for Talbot to draw the 'Leather Nun' archetype so fondly rendered in American underground comix.

Additional episodes of what was to become 'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright' ran in various short-lived, UK under- and above- ground comics in the late 70s - early 80s.

Several trade paperback compilations of the Arkwright comics were released in the UK in the 80s, but it was not until 1987 that American indie comic publisher Valkyrie released the complete Arkwright comics as a 9-issue series.

The Valkyrie series was given an underwhelming reception in the US, an outcome that may have had something to do with the formatting of the comics; in a reaction to what he saw as the sterile, contrived nature of American comics, Talbot had drawn them without speech balloons, sound effects, whoosh marks, etc.

Despite the disappointing reception of the Valkyrie imprint, Dark Horse Comics publisher Mike Richardson acquired the license to the series and decided to republish it, this time with changes to the formatting that Richardson felt would make the comic more palatable to the US readership, such as including speech balloons.

Talbot agreed to provide all-new covers for the Dark Horse series, and each issue was to contain, in addition to the comic proper, ancillary features such as essays on the Luther Arkwright phenomenon, and previews of upcoming episodes.

Dark Horse published issue #1 in March, 1990, finishing up with issue #9 in February, 1991. In July 1997 the company released all 9 comics in a trade paperback compilation.

So.....what is 'Luther Arkwright' all about ?

The plot is heavily reliant on Michael Moorcock's 'multiverse' concept, in which what may be an infinite number of parallel worlds exist, simultaneously , alongside one another in the space-time continuum. This idea is not overly novel on Moorcock's part - in the 1950s, H. Beam Piper was among the first to make the concept an integral part of sf - but Moorcock's interpretation exerted much influence on British writers in the 60s and 70s.

The 'Arkwright' adventures take place on a number of parallel worlds, or 'paras'. These are at various stages of political and technological development. A shadowy force, composed of beings of malevolent intent known as the 'Disruptors', seek to influence events on multiple paras. The ultimate goal of the Disruptors is unclear, but they are prepared to kill and maim in order to achieve it.

The most technologically advanced para, known as 'ZeroZero', watches events on the other paras with alarm, as the influence of the Disruptors grows.

In an effort to counter the influence of the Disruptors, ZeroZero decides to infiltrate the paras with its own agent for change: an agent named Luther Arkwright. Arkwright possesses esp and other paranormal abilities, which will serve him in good stead in his shadowy war against the Disruptors.

On one particular para, it's 1984, and in a London ruled by the descendent of Oliver Cromwell, the contest between the Disruptors and ZeroZero approaches critical mass. A rebellion by the remnants of the monarchy is about to emerge, even as the forces of Germany and Russia look on in anticipation of stepping in to subdue the exhausted victors and take Albion for their own.

All that stands between the Disruptors, and their takeover of the multiverse, is Luther Arkwright......

'Arkwright' is not the most accessible comic; as a product of the 70s, it's initial three issues are more of a display of the author's desire to showcase the experimental, avant-garde ethos of the underground comix movement than a coherent narrative. The storyline jumps about in time and space, and fails to provide the necessary exposition that might give the reader any orientation as to what is taking place.

Things improve from issue 4 on, as the central plot begins to take shape and a storyline emerges out of the confusion.

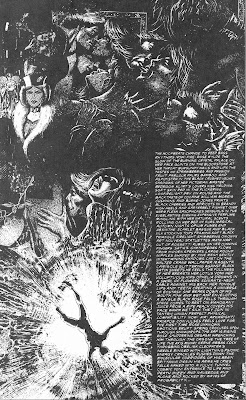

What gives 'Arkwright' its status as one of the great sf comics of the 20th century is not so much its plot - which could be classified as proto-steampunk - as its artwork. Because the series unfolded over a protracted interval of time, Talbot had the opportunity to apply his meticulous, deliberate draftsmanship in every issue.

The result is an impressive display of black and white and graytone artwork. From page to page, panel to panel, Talbot displays his skills in chiaroscuro, pen-and-ink, ink wash, and other techniques:

For example, the intricate Pre-Raphaelite motifs of the wallpaper behind Rose Wylde, in the panel below, must have taken days to complete:

In the page below, the careful placement of the individual reaction shots of the characters, superimposed on the cataclysmic event taking place in the central illustration, with its penumbra rendered in staggered layers of shading, is also very well done:

This type of draftsmanship, the dedication to cross-hatching and shading, simply doesn't exist anymore in contemporary mainstream publisher comic books. And today's 'indie' comics, that have since supplanted the underground comics of the 60s and 70s, are marked by mediocre, amateurish artwork.

Summing up: if you're a fan of old school comics and graphic art, then you'll want to pick up 'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright'.

But...... I suspect that anyone under 30 will find 'Arkwright' underwhelming, even over-rated. Compared to modern comics, the experimental nature of much of the Arkwright content will be a turn-off.....such as trying to read a page containing a block of stream-of-consciousness text set in 5-point font:

In 1999, Dark Horse Comics published a sequel to 'Arkwright', titled 'Heart of Empire'. 'Heart' ran to nine lengthy issues, from April 1999 - December 1999.

Printed on quality paper, with computer-generated coloring provided by Angus McKie, 'Heart' was much more user-friendly in its attitudes towards the modern comic book concept.

I recommend reading 'Luther Arkwright' prior to taking on 'Empire', as many aspects of the latter's narrative won't really make sense in the absence of familiarity with the preceding volume.

Complete sets of the Dark Horse series for 'Arkwright' and 'Empire' are available at the usual online outlets for reasonable prices, as are the two graphic novels that compile each of the series.

Talbot's online shop offers a variety of merchandise, including a CD that contains the complete 'Arkwright', 'Empire', plus a host of ancillary material, such as a commentary by Talbot, draft sketches, and essays. Talbot's shop also offers pages of original artwork, tee-shirts, and copies of his other graphic novels, such as the 'Grandville' books, 'The Tale of One Bad Rat', and 'Alice in Sunderland'.

The Dark Horse Comics series, March 1990 - February 1991

Graphic novel, Dark Horse, July 1997

'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright' has a complicated history.

Throughout the 1970s, British artist Bryan Talbot contributed material to various underground comix being published in the UK, among them Brainstorm Comix.

In 1976, as Talbot recounts in his history of the Arkwright canon, in an issue of Mixed Bunch Comix (a Brainstorm imprint) he drew a seven-page strip titled 'The Papist Affair'. This represented the first appearance of the Luther Arkwright character.

'The Papist Affair' was a humor strip, and in my opinion, it was mainly intended as an opportunity for Talbot to draw the 'Leather Nun' archetype so fondly rendered in American underground comix.

Additional episodes of what was to become 'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright' ran in various short-lived, UK under- and above- ground comics in the late 70s - early 80s.

Several trade paperback compilations of the Arkwright comics were released in the UK in the 80s, but it was not until 1987 that American indie comic publisher Valkyrie released the complete Arkwright comics as a 9-issue series.

The Valkyrie series was given an underwhelming reception in the US, an outcome that may have had something to do with the formatting of the comics; in a reaction to what he saw as the sterile, contrived nature of American comics, Talbot had drawn them without speech balloons, sound effects, whoosh marks, etc.

Despite the disappointing reception of the Valkyrie imprint, Dark Horse Comics publisher Mike Richardson acquired the license to the series and decided to republish it, this time with changes to the formatting that Richardson felt would make the comic more palatable to the US readership, such as including speech balloons.

Talbot agreed to provide all-new covers for the Dark Horse series, and each issue was to contain, in addition to the comic proper, ancillary features such as essays on the Luther Arkwright phenomenon, and previews of upcoming episodes.

Dark Horse published issue #1 in March, 1990, finishing up with issue #9 in February, 1991. In July 1997 the company released all 9 comics in a trade paperback compilation.

So.....what is 'Luther Arkwright' all about ?

The plot is heavily reliant on Michael Moorcock's 'multiverse' concept, in which what may be an infinite number of parallel worlds exist, simultaneously , alongside one another in the space-time continuum. This idea is not overly novel on Moorcock's part - in the 1950s, H. Beam Piper was among the first to make the concept an integral part of sf - but Moorcock's interpretation exerted much influence on British writers in the 60s and 70s.

The 'Arkwright' adventures take place on a number of parallel worlds, or 'paras'. These are at various stages of political and technological development. A shadowy force, composed of beings of malevolent intent known as the 'Disruptors', seek to influence events on multiple paras. The ultimate goal of the Disruptors is unclear, but they are prepared to kill and maim in order to achieve it.

The most technologically advanced para, known as 'ZeroZero', watches events on the other paras with alarm, as the influence of the Disruptors grows.

In an effort to counter the influence of the Disruptors, ZeroZero decides to infiltrate the paras with its own agent for change: an agent named Luther Arkwright. Arkwright possesses esp and other paranormal abilities, which will serve him in good stead in his shadowy war against the Disruptors.

On one particular para, it's 1984, and in a London ruled by the descendent of Oliver Cromwell, the contest between the Disruptors and ZeroZero approaches critical mass. A rebellion by the remnants of the monarchy is about to emerge, even as the forces of Germany and Russia look on in anticipation of stepping in to subdue the exhausted victors and take Albion for their own.

All that stands between the Disruptors, and their takeover of the multiverse, is Luther Arkwright......

'Arkwright' is not the most accessible comic; as a product of the 70s, it's initial three issues are more of a display of the author's desire to showcase the experimental, avant-garde ethos of the underground comix movement than a coherent narrative. The storyline jumps about in time and space, and fails to provide the necessary exposition that might give the reader any orientation as to what is taking place.

Things improve from issue 4 on, as the central plot begins to take shape and a storyline emerges out of the confusion.

What gives 'Arkwright' its status as one of the great sf comics of the 20th century is not so much its plot - which could be classified as proto-steampunk - as its artwork. Because the series unfolded over a protracted interval of time, Talbot had the opportunity to apply his meticulous, deliberate draftsmanship in every issue.

The result is an impressive display of black and white and graytone artwork. From page to page, panel to panel, Talbot displays his skills in chiaroscuro, pen-and-ink, ink wash, and other techniques:

For example, the intricate Pre-Raphaelite motifs of the wallpaper behind Rose Wylde, in the panel below, must have taken days to complete:

In the page below, the careful placement of the individual reaction shots of the characters, superimposed on the cataclysmic event taking place in the central illustration, with its penumbra rendered in staggered layers of shading, is also very well done:

This type of draftsmanship, the dedication to cross-hatching and shading, simply doesn't exist anymore in contemporary mainstream publisher comic books. And today's 'indie' comics, that have since supplanted the underground comics of the 60s and 70s, are marked by mediocre, amateurish artwork.

Summing up: if you're a fan of old school comics and graphic art, then you'll want to pick up 'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright'.

But...... I suspect that anyone under 30 will find 'Arkwright' underwhelming, even over-rated. Compared to modern comics, the experimental nature of much of the Arkwright content will be a turn-off.....such as trying to read a page containing a block of stream-of-consciousness text set in 5-point font:

In 1999, Dark Horse Comics published a sequel to 'Arkwright', titled 'Heart of Empire'. 'Heart' ran to nine lengthy issues, from April 1999 - December 1999.

Printed on quality paper, with computer-generated coloring provided by Angus McKie, 'Heart' was much more user-friendly in its attitudes towards the modern comic book concept.

I recommend reading 'Luther Arkwright' prior to taking on 'Empire', as many aspects of the latter's narrative won't really make sense in the absence of familiarity with the preceding volume.

Complete sets of the Dark Horse series for 'Arkwright' and 'Empire' are available at the usual online outlets for reasonable prices, as are the two graphic novels that compile each of the series.

Talbot's online shop offers a variety of merchandise, including a CD that contains the complete 'Arkwright', 'Empire', plus a host of ancillary material, such as a commentary by Talbot, draft sketches, and essays. Talbot's shop also offers pages of original artwork, tee-shirts, and copies of his other graphic novels, such as the 'Grandville' books, 'The Tale of One Bad Rat', and 'Alice in Sunderland'.

↧

Book Review: The Machine in Shaft Ten

Book Review: 'The Machine in Shaft Ten' by M. John Harrison

‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’ (174 pp) was published in the UK by Panther Books, and features cover artwork by Chris Foss. The stories it compiles were first published in the late 60s and early 70s in New Worlds and other sf magazines.

‘Machine’ is an eclectic collection that represents some of the worst, and some of the best, New Wave sf.

Of the twelve stories in ‘Machine’, four - The Bait Principle, The Orgasm Band, Visions of Monad, and The Bringer with the Window – are all ‘experimental’ fictions in which a series of loosely-connected vignettes are presented to the reader, charging him or her with fashioning their own narrative from the presented material. This sort of short story was prevalent in the New Wave era, and has aged badly.

The remaining stories in ‘Machine’ are, however, among the best Harrison has written and display the imagination and creativity that the New Wave movement brought to sf.

All of these, to one degree or another, are preoccupied with entropy, and while it’s true that the New Wave movement as a whole certainly was preoccupied with entropy, Harrison was one of the few authors who didn’t simply try to emulate J. G. Ballard, but instead injected his own interpretation of the idea into his fiction.

The stories in ‘Machine’ present entropy in striking visual terms: it’s always November; there are fields of corroded metal spars, abandoned buildings with walls encrusted with mold, fogs and mists concealing great heaps of disintegrating machinery, alienated characters seeking shelter in bombed-out ruins created by a war since forgotten, etc.

Poking through these entropic visions are sharp, nasty acts of violence and cruelty.

The lead story, ‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’, deals with the discovery of a possible alien artifact churning away deep within the earth’s core. This discovery spawns a new religious cult with ambivalent implications for the fate of humankind.

‘The Lamia and Lord Chromis’ is a Viriconium story, and today, more than 40 years later, still one of the most offbeat and imaginative fantasy stories ever written. The plot is not particularly original, but the atmosphere and themes, which borrow somewhat from Jack Vance, brought a new sensibility to the genre.

‘Running Down’, about a man afflicted with entropy, was also very creative for its time, and while overly long, and tending to belabor rock climbing (Harrison’s favorite past-time), it too remains relevant as an example of sf that extends the genre.

‘Events Witnessed from a City’ is another Viriconium tale, and while it adopts the episodic nature of the ‘experimental’ pieces, its more coherent, and delivers a uniquely downbeat ending.

In ‘London Melancholy’, a race of winged humans cautiously explore a London destroyed by a war with a race of unusual aliens. Fusing entropy with the sf trope of alien invaders, it’s one of the better New Wave stories ever written.

‘Ring of Pain’ is also set in the fog-wreathed ruins of an English city, but here, it’s a personal sort of violence visited on the survivors who crawl through the dripping ruins.

‘The Causeway’ takes place on an unnamed planet where the narrator endeavors to discover the origins and purpose of a mysterious, enormous bridge that stretches for what may be hundreds of miles across the sea. Downbeat, melancholy, and with a twist ending.

‘Coming from Behind’ is another alien invasion tale. A deserter named Prefontaine makes his way through a bleak landscape of abandoned buildings and deserted roadways, hiding from his pursuers. He discovers that his moral obligations may outweigh his interests in self-preservation.

In summary, ‘Machine’ is well worth getting, even though almost half its contents are New Wave affectations that haven’t endured well. The remaining ‘traditional’ stories more than make up for the less-impressive entries.

4 / 5 Stars

‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’ (174 pp) was published in the UK by Panther Books, and features cover artwork by Chris Foss. The stories it compiles were first published in the late 60s and early 70s in New Worlds and other sf magazines.

‘Machine’ is an eclectic collection that represents some of the worst, and some of the best, New Wave sf.

Of the twelve stories in ‘Machine’, four - The Bait Principle, The Orgasm Band, Visions of Monad, and The Bringer with the Window – are all ‘experimental’ fictions in which a series of loosely-connected vignettes are presented to the reader, charging him or her with fashioning their own narrative from the presented material. This sort of short story was prevalent in the New Wave era, and has aged badly.

The remaining stories in ‘Machine’ are, however, among the best Harrison has written and display the imagination and creativity that the New Wave movement brought to sf.

All of these, to one degree or another, are preoccupied with entropy, and while it’s true that the New Wave movement as a whole certainly was preoccupied with entropy, Harrison was one of the few authors who didn’t simply try to emulate J. G. Ballard, but instead injected his own interpretation of the idea into his fiction.

The stories in ‘Machine’ present entropy in striking visual terms: it’s always November; there are fields of corroded metal spars, abandoned buildings with walls encrusted with mold, fogs and mists concealing great heaps of disintegrating machinery, alienated characters seeking shelter in bombed-out ruins created by a war since forgotten, etc.

Poking through these entropic visions are sharp, nasty acts of violence and cruelty.

The lead story, ‘The Machine in Shaft Ten’, deals with the discovery of a possible alien artifact churning away deep within the earth’s core. This discovery spawns a new religious cult with ambivalent implications for the fate of humankind.

‘The Lamia and Lord Chromis’ is a Viriconium story, and today, more than 40 years later, still one of the most offbeat and imaginative fantasy stories ever written. The plot is not particularly original, but the atmosphere and themes, which borrow somewhat from Jack Vance, brought a new sensibility to the genre.

‘Running Down’, about a man afflicted with entropy, was also very creative for its time, and while overly long, and tending to belabor rock climbing (Harrison’s favorite past-time), it too remains relevant as an example of sf that extends the genre.

‘Events Witnessed from a City’ is another Viriconium tale, and while it adopts the episodic nature of the ‘experimental’ pieces, its more coherent, and delivers a uniquely downbeat ending.

In ‘London Melancholy’, a race of winged humans cautiously explore a London destroyed by a war with a race of unusual aliens. Fusing entropy with the sf trope of alien invaders, it’s one of the better New Wave stories ever written.

‘Ring of Pain’ is also set in the fog-wreathed ruins of an English city, but here, it’s a personal sort of violence visited on the survivors who crawl through the dripping ruins.

‘The Causeway’ takes place on an unnamed planet where the narrator endeavors to discover the origins and purpose of a mysterious, enormous bridge that stretches for what may be hundreds of miles across the sea. Downbeat, melancholy, and with a twist ending.

‘Coming from Behind’ is another alien invasion tale. A deserter named Prefontaine makes his way through a bleak landscape of abandoned buildings and deserted roadways, hiding from his pursuers. He discovers that his moral obligations may outweigh his interests in self-preservation.

In summary, ‘Machine’ is well worth getting, even though almost half its contents are New Wave affectations that haven’t endured well. The remaining ‘traditional’ stories more than make up for the less-impressive entries.

↧

↧

Blood on Black Satin episode two

↧

Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky

Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky

'Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky' (112 pp.) was published by UK's Paper Tiger 2000.

Ron Waltosky was a prolific illustrator of sf and fantasy paperbacks throughout the 70s and 80s. This volume provides a good overview of his works during that interval.

During the 70s, when Avon Books (USA) published many of Piers Anthony's works, Walotsky was the cover artist, and those readers seeing the illustrations for 'Kirlian Quest' amd other works will get a shot of Instant Nostalgia.

Needless to say, Walotsky's colorful, imaginative artwork often was featured on the covers of books by other authors.

Walotsky also provided artwork for the horror genre, as in this cover for Stephen King's 'Carrie':

In addition to covers for paperbacks, Walotsky also handled commissions for posters and studio art pieces:

The 1990s saw him providing cover art for sf magazines:

One of the more impressive cover paintings Walotsky did was for this 1988 sf novel:

As well as one of the more memorable covers ('Tightrope') for Heavy Metal magazine (the October, 1978 issue).

'Inner Visions', like all the Paper Tiger art books, is printed on quality paper stock and the printing of the reproductions is very good. Fans of sf and fantasy artwork will want to have a copy.

'Inner Visions: The Art of Ron Walotsky' (112 pp.) was published by UK's Paper Tiger 2000.

Ron Waltosky was a prolific illustrator of sf and fantasy paperbacks throughout the 70s and 80s. This volume provides a good overview of his works during that interval.

During the 70s, when Avon Books (USA) published many of Piers Anthony's works, Walotsky was the cover artist, and those readers seeing the illustrations for 'Kirlian Quest' amd other works will get a shot of Instant Nostalgia.