Book Review: 'The Dying Earth' by Jack Vance

4 / 5 Stars

This paperback edition of ‘The Dying Earth’ (which was originally published in 1950) was released by Lancer Books in 1962, and features cover artwork by Ed Emshwiller.

This is the first volume in what is now known as the ‘Dying Earth’ tetralogy, the other volumes being ‘The Eyes of the Overworld’ (1966), ‘Cugel’s Saga’ (1983), and ‘Rhialto the Marvellous’ (1984).

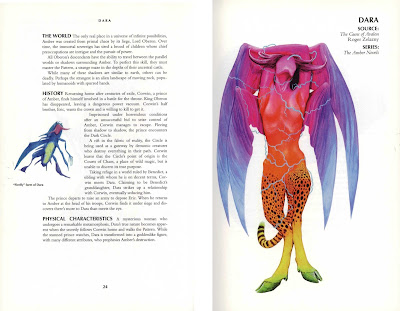

‘The Dying Earth’ is comprised of eight loosely connected stories, all set in the fantasy landscape of a far-future Earth, in which the Sun is a sullen red ball, bereft of energy. Millennia have passed since the 20th century, and much of Man’s achievements long have been buried by the passage of time. There are still sizeable cities scattered around the globe, but the lands between are either wasteland or wilderness, inhabited by various monsters and bands of troglodytes. Whatever technology still exists is that scrabbled from the remnants of long-dead empires.

The cities are by no means entirely safe, for wizards are plentiful ,and operate outside the boundaries of what little law remains. Throughout the ‘Dying Earth’ novels, much of the action revolves around the efforts of various protagonists to free themselves from some obligation or debt made to a cunning, often pitiless wizard.

Most of the stories in ‘Dying’ range in mood and theme. The first three tales, ‘Turjan of Miir’, and continuing with ‘Mazirian the Magician’, and ‘T’Sais’, center on action and adventure, as their protagonists seek to overcome the machinations of evil magicians.

‘Liane the Wayfarer’ is an effective horror story. ‘Ulan Dhor’ and ‘Guyal of Sfere’ tend more towards a fantasy / sci-fi tenor, as these characters venture into the ruins of former civilizations possessed of wondrous technologies.

For stories first written in 1950, the entries in ‘The Dying Earth’ have a very modern prose styling, and are markedly superior to the sf of their time, which was still centered on a pulp approach to characterization and plotting. This being Vance, of course, readers will need to have Google handy to look up obscure adjectives and adverbs. However, the writing adeptly mixes descriptive passages with a concise, fast-moving sense of plotting and pace, something lacking to a large extent in modern fantasy literature.

Copies of ‘The Dying Earth’ in good condition can be expensived; I recommend obtaining the omnibus edition, ‘Tales of the Dying Earth’ (2000), available from Orb Books; this trade paperback is affordable.

4 / 5 Stars

This paperback edition of ‘The Dying Earth’ (which was originally published in 1950) was released by Lancer Books in 1962, and features cover artwork by Ed Emshwiller.

This is the first volume in what is now known as the ‘Dying Earth’ tetralogy, the other volumes being ‘The Eyes of the Overworld’ (1966), ‘Cugel’s Saga’ (1983), and ‘Rhialto the Marvellous’ (1984).

‘The Dying Earth’ is comprised of eight loosely connected stories, all set in the fantasy landscape of a far-future Earth, in which the Sun is a sullen red ball, bereft of energy. Millennia have passed since the 20th century, and much of Man’s achievements long have been buried by the passage of time. There are still sizeable cities scattered around the globe, but the lands between are either wasteland or wilderness, inhabited by various monsters and bands of troglodytes. Whatever technology still exists is that scrabbled from the remnants of long-dead empires.

The cities are by no means entirely safe, for wizards are plentiful ,and operate outside the boundaries of what little law remains. Throughout the ‘Dying Earth’ novels, much of the action revolves around the efforts of various protagonists to free themselves from some obligation or debt made to a cunning, often pitiless wizard.

Most of the stories in ‘Dying’ range in mood and theme. The first three tales, ‘Turjan of Miir’, and continuing with ‘Mazirian the Magician’, and ‘T’Sais’, center on action and adventure, as their protagonists seek to overcome the machinations of evil magicians.

‘Liane the Wayfarer’ is an effective horror story. ‘Ulan Dhor’ and ‘Guyal of Sfere’ tend more towards a fantasy / sci-fi tenor, as these characters venture into the ruins of former civilizations possessed of wondrous technologies.

For stories first written in 1950, the entries in ‘The Dying Earth’ have a very modern prose styling, and are markedly superior to the sf of their time, which was still centered on a pulp approach to characterization and plotting. This being Vance, of course, readers will need to have Google handy to look up obscure adjectives and adverbs. However, the writing adeptly mixes descriptive passages with a concise, fast-moving sense of plotting and pace, something lacking to a large extent in modern fantasy literature.

Copies of ‘The Dying Earth’ in good condition can be expensived; I recommend obtaining the omnibus edition, ‘Tales of the Dying Earth’ (2000), available from Orb Books; this trade paperback is affordable.