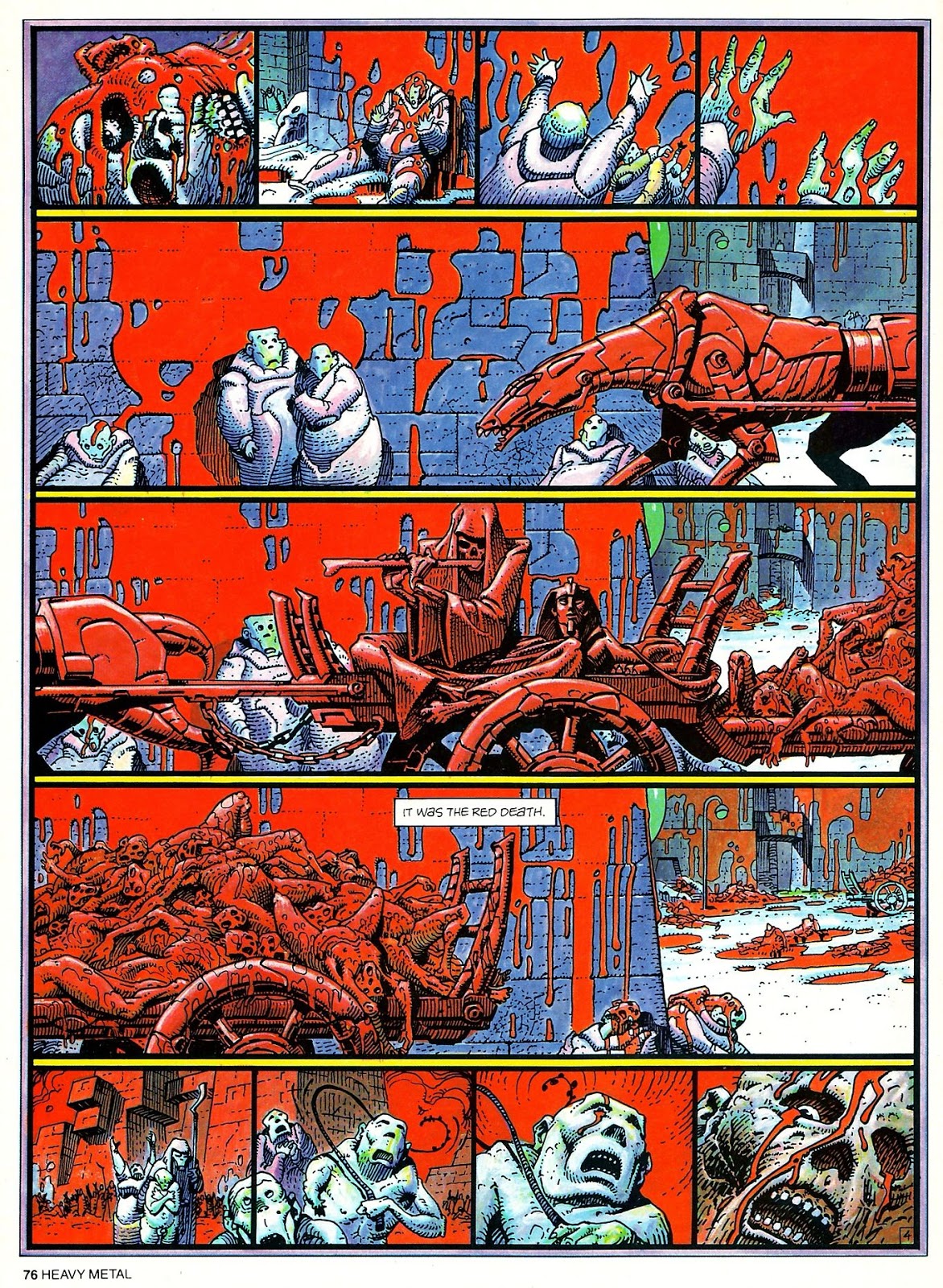

'Heavy Metal' magazine September 1979

September, 1979, and selected FM radio stations are playing the song 'Hold On' by Ian Gomm.

The latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is available at Gordon's cigar store, and I eagerly pick it up.

Jim Cherry provided the front cover, ‘Love Hurts’, while the back cover is an untitled painting by Val Mayerik. There's a full-page advertisement for the Car's new album 'Candy-O', featuring a Vargas Girl sprawled atop the engine of a sports car. Crude sexual exploitation, or cool marketing ? In the 70s, they didn't really care.....

The September, 1979 issue is a good issue, with 'Only Connect: The Spirit of the Game' by Alias, 'The Doll' by J. K. Potter, 'Little Red' by He, 'Soft Landing' by Warkentin and O'Bannon, 'Airtight Garage' by Moebius, and 'Telefield' by Sergio Macedo.

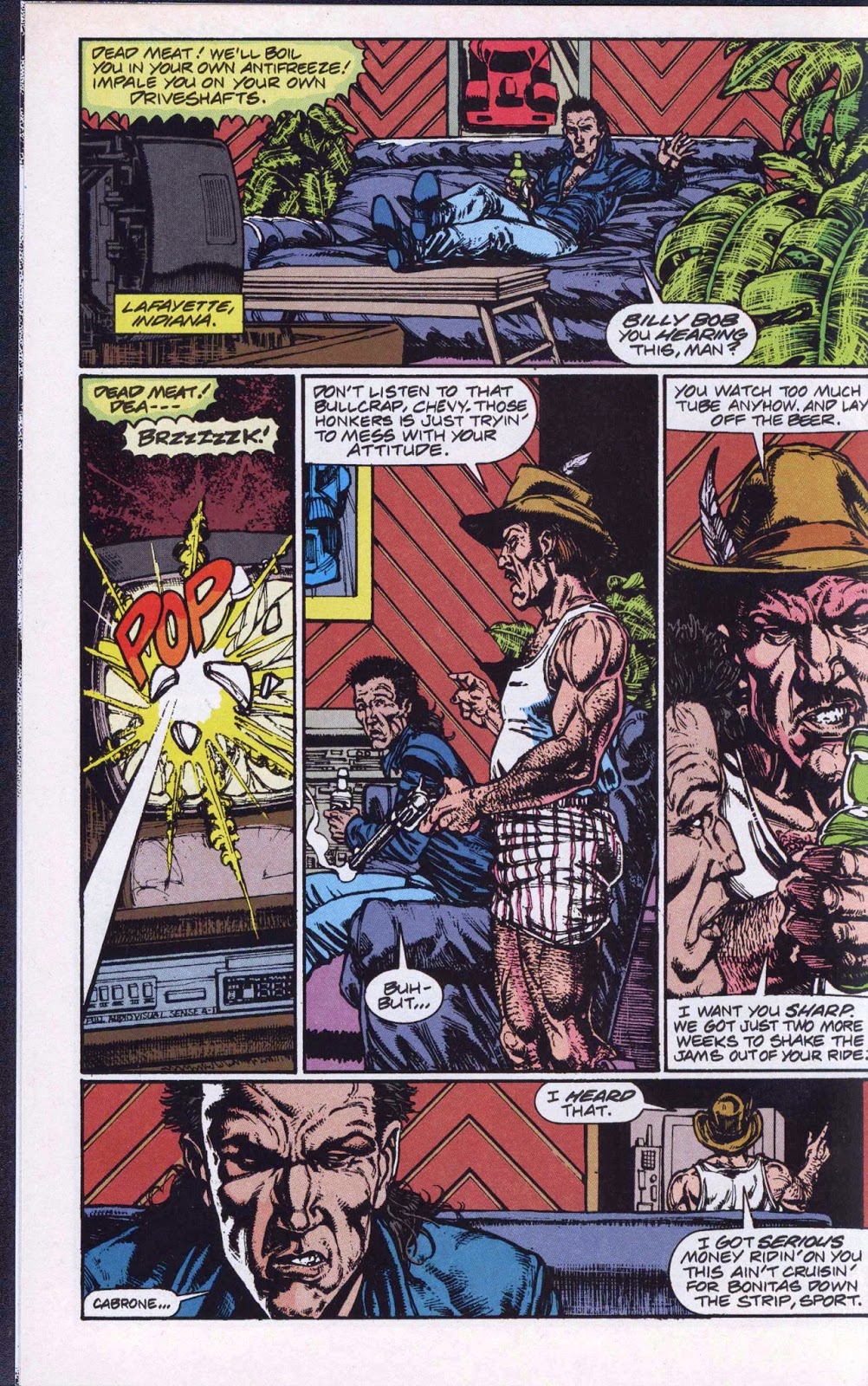

Among the better comics was a one-and-only episode of 'Buck Rogers in the 25th Century: On the Moon of Madness' by Gray Morrow and Jim Lawrence. I've posted it below.

September, 1979, and selected FM radio stations are playing the song 'Hold On' by Ian Gomm.

The latest issue of Heavy Metal magazine is available at Gordon's cigar store, and I eagerly pick it up.

Jim Cherry provided the front cover, ‘Love Hurts’, while the back cover is an untitled painting by Val Mayerik. There's a full-page advertisement for the Car's new album 'Candy-O', featuring a Vargas Girl sprawled atop the engine of a sports car. Crude sexual exploitation, or cool marketing ? In the 70s, they didn't really care.....

The September, 1979 issue is a good issue, with 'Only Connect: The Spirit of the Game' by Alias, 'The Doll' by J. K. Potter, 'Little Red' by He, 'Soft Landing' by Warkentin and O'Bannon, 'Airtight Garage' by Moebius, and 'Telefield' by Sergio Macedo.

Among the better comics was a one-and-only episode of 'Buck Rogers in the 25th Century: On the Moon of Madness' by Gray Morrow and Jim Lawrence. I've posted it below.